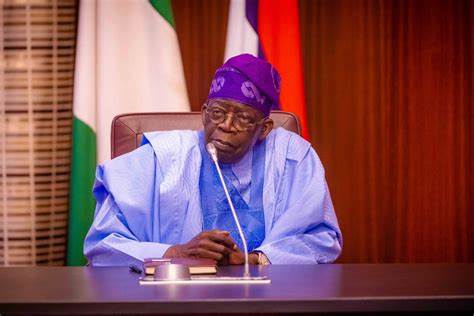

The Presidency has moved to clarify widespread misconceptions about President Bola Tinubu’s $24 billion borrowing proposal, emphasizing that it represents a comprehensive three-year planning framework rather than an immediate loan request.

The clarification comes amid mounting criticism from opposition parties and political elites who expressed concern that the proposed borrowing could add approximately ₦38.24 trillion to Nigeria’s existing debt stock. Critics warned this could potentially push the country’s total public debt from ₦144.67 trillion at the end of 2024 to over ₦182.91 trillion by 2026.

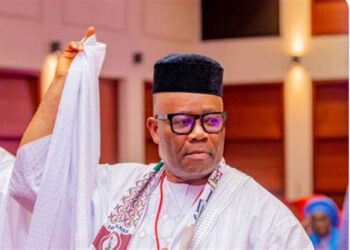

Senior Special Assistant to the President on Media, Tope Ajayi, addressed these concerns during an interview on ‘Real Talk With Kike,’ explaining that the President is not seeking to borrow a fresh $24 billion but has instead presented a strategic borrowing plan to the National Assembly as required by law.

“The administration is not borrowing $24 or $21 billion. Under the fiscal responsibility law, the government sends the borrowing plan to the National Assembly. It is a plan, not that the government will borrow tomorrow,” Ajayi explained. He emphasized that the framework operates under the Fiscal Responsibility Law, which mandates that the federal government submit its borrowing plans to the National Assembly without necessarily triggering immediate borrowing.

The presidential aide revealed that the $24 billion plan encompasses not just the federal government but includes borrowing projections for state governments and the Federal Capital Territory. This comprehensive approach reflects the constitutional reality that only the President has the authority to secure external loans on behalf of all tiers of government.

“It is not the federal government borrowing alone; it is a plan that includes both the federal and state governments. It is a three-year borrowing plan,” Ajayi stated. “The president cannot go to the National Assembly every quarter or six months to discuss borrowing. The law makes provision for the president to present a three-year borrowing plan that includes the states and FCT.”

The clarification comes as the administration seeks to demonstrate fiscal responsibility and transparency in its debt management approach. Ajayi noted that presenting such plans allows for proper legislative oversight and public debate before any actual borrowing decisions are made.

“In the three-year borrowing plan, the President has incorporated the plans of every state into it, and it is presented to the National Assembly for review, debate, and approval. The fact that you have a plan does not necessarily mean the money will be taken, but it is good for planning,” he added.

The Presidency also highlighted recent debt reduction efforts to counter narratives about increasing Nigeria’s debt burden. According to Ajayi, the federal government recently paid $3.4 billion to settle an IMF loan taken during the COVID-19 pandemic and cleared ₦300 billion in Sukuk Islamic bonds.

These payments, along with ongoing debt servicing, are being funded through savings realized from the removal of fuel subsidies, a key policy initiative of the Tinubu administration. “The federal government and states, including FCT, are paying down on their debt due to money realized from the fuel subsidy,” Ajayi explained.

The fuel subsidy removal has generated significant additional revenue that is being distributed across all levels of government. “Many states are able to fund their projects and pay salaries because of the policy of fuel subsidy removal. The money saved from fuel subsidy are the funds the federal, state and local governments are using,” the presidential aide noted.

The controversy surrounding the borrowing plan reflects broader concerns about Nigeria’s debt sustainability and fiscal management. While the opposition has raised alarm about potential debt accumulation, the Presidency maintains that its approach prioritizes strategic planning and transparency in government borrowing decisions.

As the National Assembly continues to review the three-year borrowing framework, the debate highlights the ongoing tension between Nigeria’s development financing needs and concerns about debt sustainability in Africa’s largest economy.